While the United States continues to progress with its war against Iraq, many Americans have seen the emotionally charged images of POWs boarding planes to return home to their families broadcast on television.

Most people will never experience the psychological trauma that comes from being a POW and the effect it has on readjusting to daily life.

For Hermosa Beach resident Ron Arias, life with a former POW is something he knows all too well. Arias is the son of an Army major who spent time in prisoner camps during two different wars and survived both experiences.

Despite Armando Arias’ efforts to leave those memories in the past, his behavior created heartaches for the family that would last for years to come.

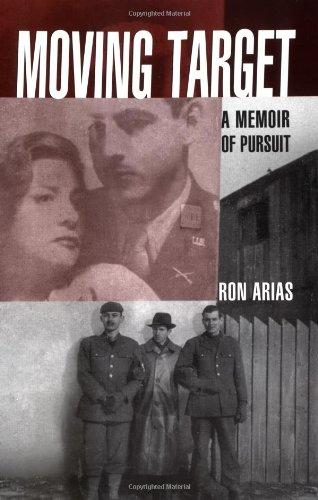

In the memoir entitled “Moving Target,” Arias chronicles the secret life of his father, who left the family in 1969 after the mysterious and suspicious death of his wife and Arias’ mother, Emma.

Arias, now 61, grew up as a child of the military mostly in Los Angeles. Arias began writing at the age of 9 while bedridden in a Camp Pendleton hospital recovering from a tonsillectomy.

“My mom gave me a notebook and told me to write down some short stories,” Arias said. “I came up with some creative stuff because I had nothing else to do there.”

Arias and his two brothers grew up in a very strict, religious household where they never challenged their father, an officer with Army Intelligence. Arias’ father served in both World War II and the Korean War.

“In looking back it was like living with the ‘Great Santini’ in that we never questioned my father, there was never any dialogue about anything. His word was law,” recalled Arias. “We had a lot of secrets in my family like many other families, and later in my life I began to discover the root cause for certain things and everything started to come full circle.”

Arias’ father, a spy, specialized in becoming a POW of the Germans, then escaping to report their movements and troop power. In Korea, he served as a platoon leader where the enemy captured him. He spent three years in a prisoner-of-war camp located along the border of China and North Korea.

In 1953, he came home to a wife who always believed he would return as expressed in her daily journal entries addressed to her husband, found years later by Arias.

“The Army told her my father was as good as dead, but she never gave up hope,” said Arias.

While living in the camp, Armando endured several beatings as the leader of three escape attempts. He also lost some of his teeth due to malnutrition. Upon his return, a fellow POW accused him of consorting with the enemy. A panel of senior Army officers then conducted a weeklong hearing to investigate numerous accusations brought forth by one man. The panel eventually cleared Arias’ father of all charges subsequent to the testimonies of more than 40 ex-POWs.

With the lingering memories of war and the stress related to the hearings, Arias’ mother and father grew distant and their marriage began to collapse.

Army officials overlooked Arias’ father when it came to promotions and the family followed him from one bleak post to the next.

Arias left home at the age of 17 and traveled the world for a time. While hitchhiking in Spain, he met Ernest Hemingway and shared a glass of wine with him. He began writing for the Buenos Aires Herald by the time he turned 20.

In 1969, Arias, now in his late 20s, got word his mother died from suspicious causes. She was only 48 and many of Arias’ aunts and uncles believed his father killed her. During this same time, Arias discovered Armando was not his biological father, whom he later met in 1970.

“I never thought of him as a stepfather. Fatherhood is how you feel about someone,” said Arias. “I think a subtheme in the book is all of those mentors in my life who were like fathers to me and influenced me.”

Following the death of Arias’ mother, his father attempted suicide and then abandoned his grown sons, never to see them again.

“Things between us were left inconclusive and after my mom’s funeral I flew back to Washington, D.C., with my wife where we were living at the time,” Arias said. “My father then attempted suicide practically on my mother’s grave. He slipped into a coma and a week later he came out of it. I really don’t know why he left and disappeared from our lives. Perhaps it was the accusations that he had killed my mother.”

Arias continued with his career in journalism, procured a position with People magazine in 1985 and migrated to New York City. He soon became curious about his father and began to track his whereabouts. He later discovered Armando died alone living as a hermit on a mountainside in Ojai.

“I use whatever time I had to find him and I would use my time traveling on assignment to interview people living in different cities who knew him,” said Arias. “I later had the Pentagon release transcripts of those hearings. I wanted to know why he left us.”

In light of his father’s death, Arias spent the next 15 years uncovering many secrets of his life through research and numerous interviews with Armando’s fellow soldiers and friends.

“I was kind of backed into the idea of writing a book and I didn’t know this at first,” said Arias. “One chapter led to another and, this is such a clich, but the characters began to have a life of their own.”

Arias initially wanted to research his father’s life as a way of grappling with questions left unanswered by his now-deceased parents. He gathered so much information he thought of writing another book. It would have been his third book with two previous nonfiction works already published.

“I was very satisfied with what I found and I found great relief to get it all answered,” explained Arias. “I don’t think I could have done this research if they (parents) were alive and I never meant to write a book, I just wanted to find some answers.”

In 1998, Arias moved to Hermosa Beach and began his work on the novel. He first thought of writing a screenplay, but finally decided on a memoir.

“I had so much material I thought of writing a play, a script, a novel and then I came up with part memoir, part detective story and part documentary,” said Arias. “A lot of it reads like a novel though.”

In 2000, Arias took a six-month sabbatical from People and completed “Moving Target.” Arias said one of the most emotional portions of the book is the epilogue where he talks earnestly about the death of his own child, one of two sons.

“Perhaps it’s something in the air, but as soon as I moved to Hermosa Beach I was able to write and finish the story,” remembered Arias. “At this time I was just reporting for People and so I didn’t have the stress of writing articles.”

Harper Collins expressed an interest in publishing “Moving Target” but Arias opted for the more academic, Bilingual Press that promised to keep the book in print.

Arias is also the author of “The Road to Tamazunchale,” nominated for a National Book Award, and “Five Against the Sea.”

“I like staying engaged with real people rather than fictional characters,” added Arias. “I guess I’m just very curious about how people survive life’s calamities.”